Jerusalem in the 19th Century

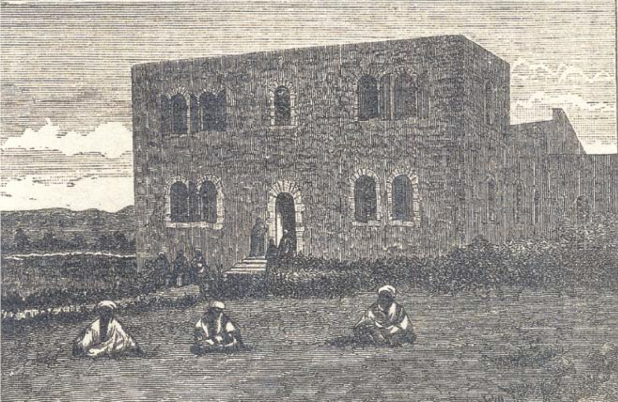

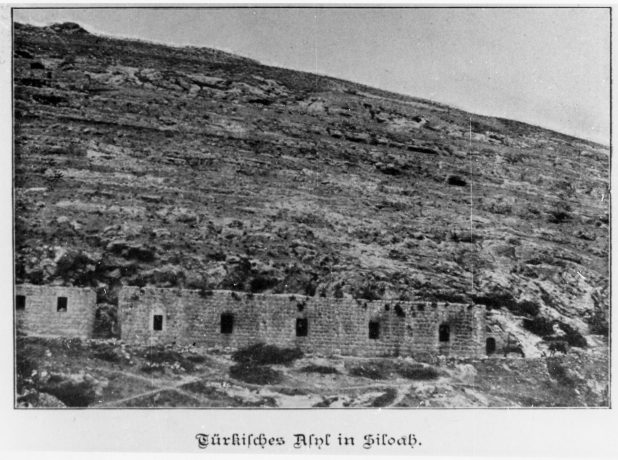

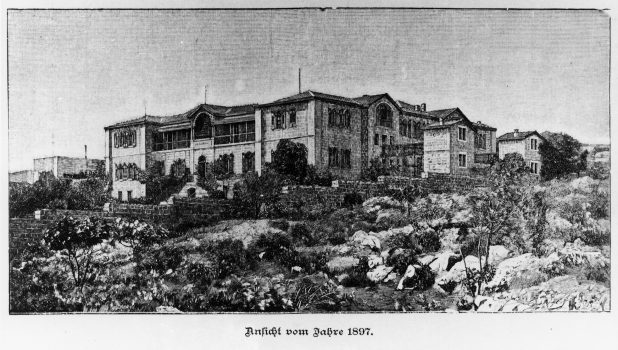

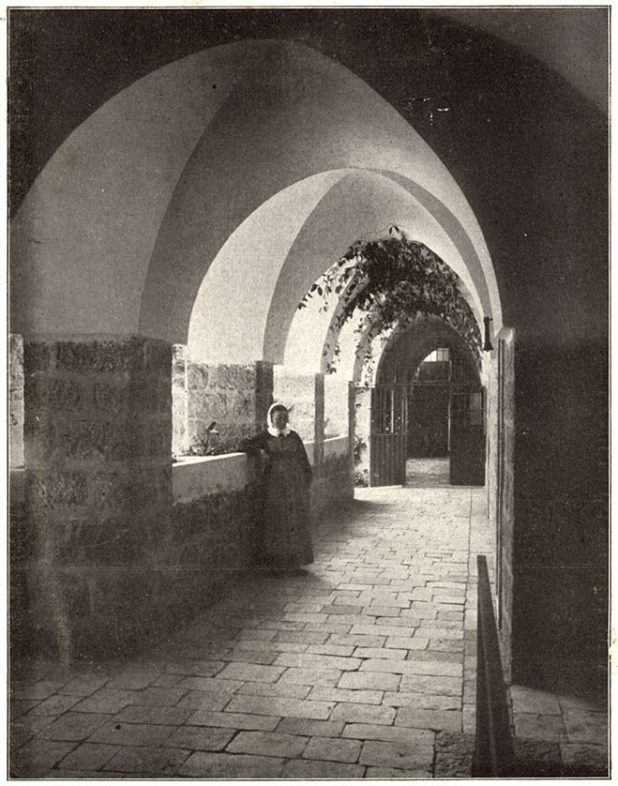

In the early 19th century, Jerusalem, a city sacred to the three monotheistic religions, was a rundown city on the periphery of the Ottoman Empire. The growing involvement of European powers in the region during the 19th century, and the competition to control it, led to the establishment of a wide range of institutions that impacted religious life, culture, education, the economy, and health conditions in the city. The local population, which previously only had access to folk medicine, began enjoying modern medical treatment in institutions established by various European bodies. Beginning in the mid-19th century, 19 hospitals were established in Jerusalem; among them was the first leper asylum, which was founded in 1867 by the Joint Anglican-German Protestant Community in Jerusalem.